On Repetition and Play

Compositions for spiritual richness

“Because the more appealing toys are, in the ordinary sense of the term, the further they are from genuine playthings; the more they are based on imitation, the further away they lead us from real, living play.” (Walter Benjamin “Cultural History of Toys”)

Every day, morning and evening, Ulysses and Helena want to repeat the same play. And within the play, we repeat the same actions over and over again.

I have been reading the same stories in the same books, their favorites, every evening for over a month now.

Every night, they ask me to sing the same song I've been singing since Ulysses was born. Even when I introduce other ones or improvise something new, I have to finish with the repetition of that one favorite melody.

In all these repetitions, there is play. Through reworking and reassessing what they already experienced, they find the space to encounter what is new, the unique feelings of that day. [1]

When I did the artwork Food for the Spirit at the Soil Factory in September, I invited the artists in the Art Share group to paint on a large canvas that I wrapped up on my body. Before starting, Ben Altman asked me if they were supposed to do it in a ritualistic way. I answered that no, that this was a playful moment. Although spontaneous and without planning, this conversation reflected directly on the space I'm constantly searching for in my work: the elusive experience of freedom. This experience touches on the most profound human spiritual capacity, perhaps, then, being available through rituality. Yet, in daily life, while performing the most repetitive of my everyday tasks, it is through play that I access it.

Walter Benjamin wrote on the difference between play and ritual, considering the perspective of repetitions. First, he considered the connection between play and ritual materially through history, arguing that "the oldest toys (...) are in a certain sense imposed on (…) [a child] as cult implements that became toys only afterward." [2] Then, he defended that play broke with the ritualistic element by introducing endless symbolic possibilities to the same object. Imagine a statue once created to represent a specific god given to a child who will, over time, make that statue into all sorts of different characters. The repetition of play expands the symbolic capacity of an object through our ability to create new contexts and establish new connections. [3]

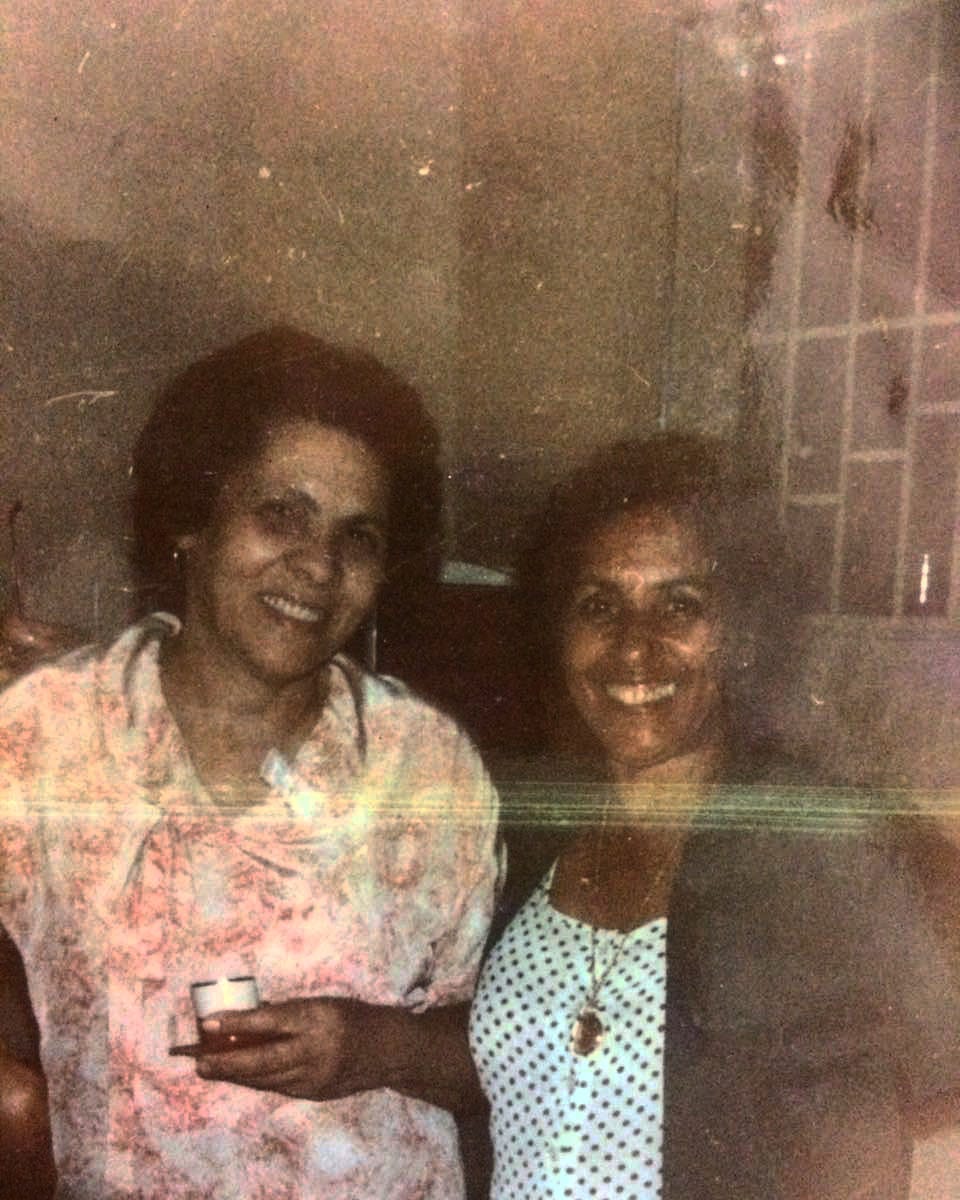

When I became a mother, I started to reach back to my grandmothers to find models for how to habit the house and stay in a family. My mother was a "working woman," and the right to divorce was part of her generational legacy. While I honor her life and choices, which were the right ones for us all at the time, I lacked an immediate model of how to accept the daily repetitive tasks of domestic life, which my grandmothers did with pride and expertise. Their sewing and knitting were of the most excellent quality, their cooking extraordinary, their cleaning and organizing skills created warm and welcoming homes, and their social skills took their families out of homelessness and hunger, securing education and social status for their children.

Looking back at my grandmothers' lives, I see the acceptance of repetition through the joy of creating beauty and harmony, through the playful moments that establish new connections within the repetitive acts, and the slight variations that transform outcomes. I don't mean to romanticize and diminish their hardship, which I know was tremendous. Yet, I recognize in their work and care for their families a serenity that remains from Indigenous knowledge: that the repetitive work not only builds the materiality of life but also carries forward our spiritual connections and legacy.

The Western art world has often pathologized the artist's need for repetition as "obsession," while the "widespread spiritual poverty" [4] that defines our capitalist condition continues to reduce rituals to simple morning routines, with an oversimplified and empty idea of the "zen." Through my children's play and my art-making, I rekindle the fire of our ancestry and the continuous presence of spirituality in the life of art.

References:

[1] I made some of these connections while I read Denise Carrascosa's "Corpo de Vento. Exu na Teoria," in which she elaborates on the connection between repetition and play while studying the Yoruba Erês, the spiritual entity of children. Carrascosa is the one who first brought to me the connection between repetition and play with Benjamin and, even more importantly, revealed the spiritual importance of it. Denise Carrascosa, Corpo de vento: Exu da teoria. SciELO - EDUFBA, 2024.

[2] Benjamin, W., 1928: Toys and Play, in Selected Writings. Volume 2, Part 1: 1927-1930, ed. by M.W. Jennings, H. Eiland, G. Smith, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.)-London, 2005, pp. 117- 121.

[3] I found in Marina Montanelli's article "Walter Benjamin and the Principle of Repetition" an excellent overview of Benjamin's connection between repetition, play, and ritual. [M. Montanelli (2018) Walter Benjamin and the Principle of Repetition. Aisthesis 11(2): 261-278. doi: 10.13128/Aisthesis-23419]

[4] Nemonte Nenquimo clearly defined my understanding of our contemporary suffering and confusion with this expression.